The Pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s Disease

Pathophysiology is the medical term for changes in the body that are caused by a disease. The pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s is complex. Learn more here.

How common is Alzheimer’s disease?

Alzheimer’s disease accounts for most of the dementia in older people and is increasingly common with age. Up to 17 percent of people between the ages of 75 to 84 have the disease, as do 32 percent above the age of 85. It is twice as common among women as among men, in part because women live longer. When Alzheimer’s runs in the family, symptoms are more likely to begin under the age of 65.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE: 10 Early Signs of Alzheimer's

What causes Alzheimer’s?

Genes are at work — we know of at least five spots in human DNA that influence the illness. Low hormone levels or exposure to metals may be factors, but these risks are not yet clear.

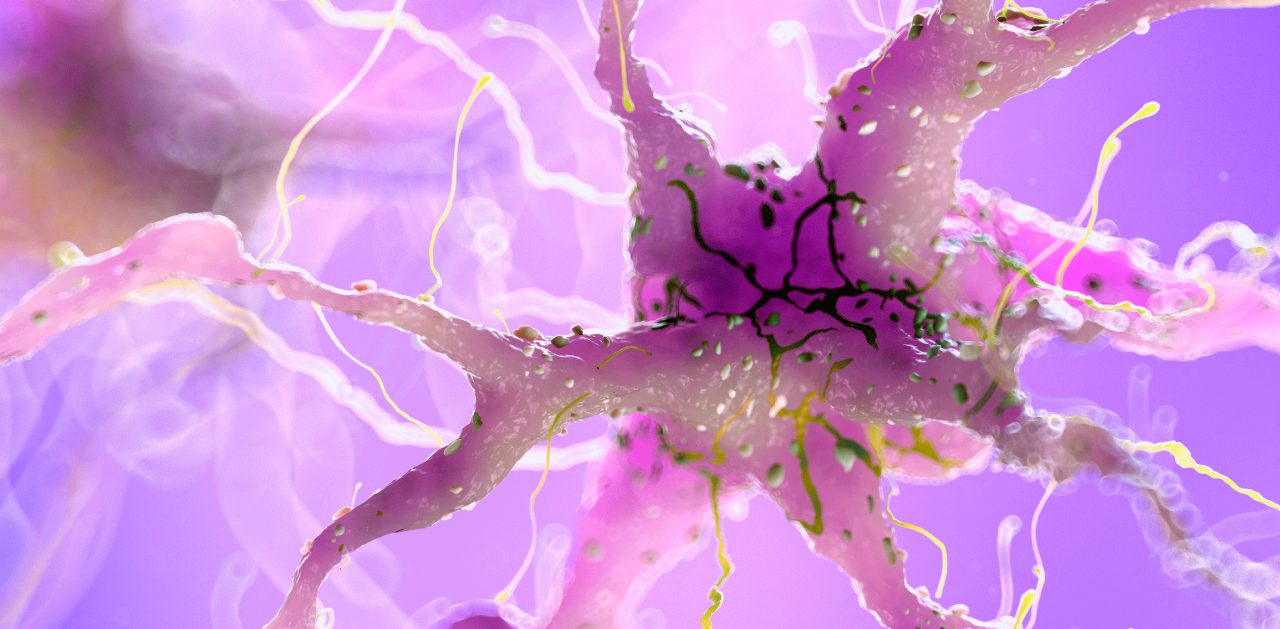

People with Alzheimer’s disease have beta amyloid plaques — hard clumps made of protein fragments, stuck between the nerve cells (also called neurons) in the brain. Beta amyloid, specifically, is a fragment from a protein called APP. Normally, beta amyloid would break down into small strands that dissolve into the fluid between cells and wash away. The fragments that clump in Alzheimer’s patients are larger. Variations in the genes that govern related proteins may create the larger fragments and clumping.

People with Alzheimer’s disease also have intracellular neurofibrillary tangles, twisted fibers mainly made of a protein called tau. The tangles appear inside the nerve cells, not between them. Tau is part of their structure, but in Alzheimer’s patients it incorrectly forms a C-shape in the core of the tangle with a loose end sticking out randomly. You can see drawings of plaques and tangles in this video from the National Institute of Aging.

It is possible that the beta-amyloid in the dangerous deposits and tau in neurofibrillary tangles reproduce themselves. When beta-amyloid reaches a tipping point, tau spreads rapidly throughout the brain.

The affected nerve cells stop working, lose connections with other nerve cells, and die. Normally, the brain shrinks as we age but doesn’t lose many nerve cells.

The damage usually begins in the part of the brain most important for memory, before moving to areas responsible for language, reasoning, and social behavior.

Tangles and plaques may not be the only cause of Alzheimer’s or may be symptoms of a more basic cause. In a healthy brain, cells called microglia destroy waste-like beta-amyloid plaque. We don’t know why they fail to do this job in Alzheimer’s patients. People with dementia also usually have problems that affect blood vessels and may have vascular dementia along with Alzheimer’s.

Symptoms of Alzheimer’s

The first early symptom is a loss of short-term memory. It is normal for aging people to suffer some memory loss. People who progress to Alzheimer’s ask the same questions repeatedly, misplace objects, forget appointments, have trouble summoning up common words, and lose the ability to identify faces or objects. Eventually they develop odd behavior like wandering and yelling. They may become paranoid and accuse caregivers of hurting them.

A standard neurologic exam and history should allow a doctor to diagnose Alzheimer’s rather than another kind of dementia, such as vascular dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies. Some people have more than one kind simultaneously. Doctors look for problems in more than two areas of cognition without any other explanation like a tumor or stroke. The symptoms appear gradually and get worse over months. Other clues include a low level of beta-amyloid in cerebrospinal fluid, high levels of tau protein, brain deposits that show up in a positron emission tomography (PET) scan, low cerebral metabolism in a part of the cortex measured by PET scan, and shrinking in key parts of the brain as detected by MRI. You or your loved one should have lab tests to rule out HIV, syphilis, or other possible causes for symptoms.

Treatment for Alzheimer’s includes medication and a supportive safe environment. Family caregivers should get training and recognize when they need support.

Available medications include memantine, combined with one of three possible cholinesterase inhibitors: donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine. There have been investigations of the effectiveness of high-dose vitamin E, Ginkgo biloba extracts, statins, selegiline, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Updated:

February 25, 2020

Reviewed By:

Janet O’Dell