Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for Autism: Fact or Fiction?

Researchers are studying how transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) affects the brain. But it’s not yet approved as a safe, effective therapy for autism.

If you’ve never heard about transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), the idea that zapping a person’s brain with magnetic fields to treat a medical disorder may sound like something out of a sci fi story — or a completely bogus quack therapy. However, TMS is real.

It’s being used to treat severe depression and also being studied to see if it can potentially help other conditions, including autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

But while TMS is approved for treating serious depression, the idea that transcranial magnetic stimulation can cure, or even improve, autism remains fiction for now.

Here’s what you need to know about TMS and how to tell if claims about transcranial magnetic stimulation for autism are fact or fiction.

How transcranial brain stimulation works

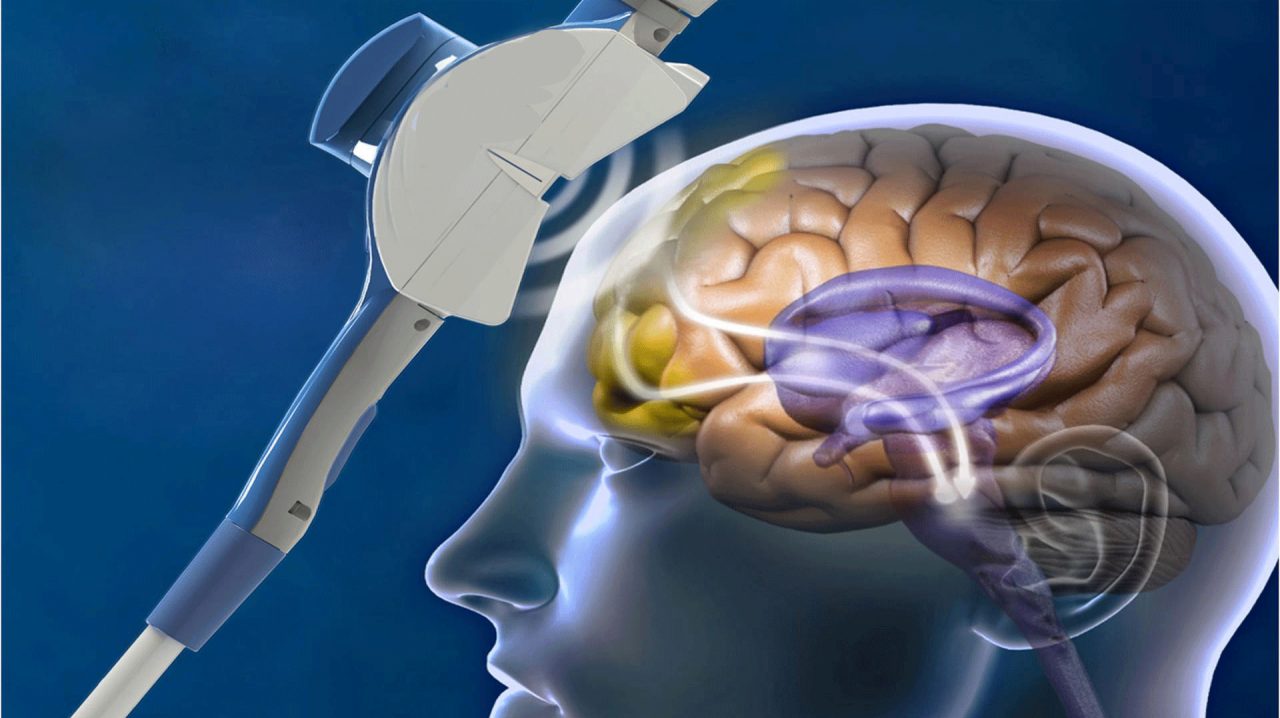

TMS is a painless and noninvasive procedure that uses magnetic fields to stimulate nerve cells in the brain. An electromagnetic coil is positioned near a patient’s forehead against the scalp. Then an electromagnet is turned on, sending a magnetic pulse to stimulate nerve cells in specific regions of the brain. Because transcranial magnetic stimulation involves magnetic pulses that are repeated, it is often called repetitive TMS (rTMS).

Transcranial magnetic stimulation was first developed in 1985. Since then, TMS has been studied as a treatment for depression, psychosis, anxiety, and other disorders. In 2008, rTMS was approved by the Food and Drug Administration as a treatment for severely depressed patients who have not responded to antidepressant medications, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) explains.

Exactly how rTMS works to relieve depression isn't completely understood. But research suggests electromagnetic stimulation eases depression symptoms and improves mood due to the impact of rTMS on regions of the brain associated with decreased activity when people suffer from depression.

Because the transcranial magnetic stimulation does appear to affect the biology of the brain, interest has been raised by both scientists and people affected by autism to find out if transcranial electromagnetic stimulation could help treat autism.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE: Early Signs of Autism

So far, research doesn’t support transcranial brain stimulation for autism

About one in 68 children has autism spectrum disorder. It’s defined as a group of complex neurodevelopment disorders characterized by repetitive, characteristic patterns of autistic behavior and difficulties with social communication and interaction. It usually develops in early childhood and can result in a wide range of symptoms, from mild to severe, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) explains.

Unfortunately, there’s no cure for ASD yet, although behavioral interventions and therapies, and sometimes medication, can help improve symptoms. Research, however, is being conducted on many fronts to learn more about what areas of the brain are affected when a person has autism, to hopefully find a cure. Transcranial brain stimulation for autism is one of the potential therapies of interest to researchers.

Several studies have looked at whether using rTMS to target a specific area of the brain, the cortex (which plays a key role in attention, perception, awareness, thought, memory, and language), could lead to improvement in behavior associated with autism symptoms. So far, studies have shown mostly mixed results using rTMS experimentally for autism symptoms.

In an analysis of studies looking at how rTMS might help autism, published in the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, Harvard Center for Noninvasive Brain Stimulation neurologists concluded some of the research is promising and might one day lead to ways to treat specific behavioral deficits associated with autism. But they had several caveats.

First, most of the studies have been done in adults and older children. In addition, while side effects (like sore muscles of the scalp, jaw or face, brief dizziness, and mild headaches) do not appear to be lasting or serious, potential long-term side effects are unknown.

What’s more, there is concern that using rTMS on the developing brains of young children could have unintended, worrisome, and even dangerous consequences.

“Caution is warranted when applying such potentially powerful modulatory effects on the brain, especially the brain of a developing child, as results have ranged from improvement to significant exacerbation of symptoms,” the Harvard neurologists wrote. “As technology advances and we are able to have a direct effect on brain functioning, we must critically evaluate the potential for benefit, while being respectful of the incredibly complex workings of the brain.”

Bottom line? Transcranial magnetic stimulation for autism is not currently fact

The good news is researchers are working on multiple fronts to better understand autism and develop better therapies and, hopefully, a cure. For example, NINDS researchers are studying aspects of brain function and development that are altered in people with ASD. Other studies are using brain imaging to identify differences in brain connectivity and activity patterns in people with and without ASD. By understanding these differences, they may be able to identify new therapeutic interventions.

Whether transcranial magnetic stimulation will become one of these therapies remains to be seen. But it is not now a proven, safe treatment. Any claim rTMS can treat and even cure autism is fiction — and any treatment using rTMS to treat autism could potentially be risky.

The Autism Science Foundation, which supports a wide range of autism research, warns that because transcranial magnetic stimulation is relatively new, long-term side effects, if any, are unknown. So, while investigations into the efficacy of transcranial magnetic stimulation for treating autism are underway, the Autism Science Foundation says there is no present evidence to support its use.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE: Debunking Homeopathic Treatments for Autism

Updated:

July 21, 2021

Reviewed By:

Janet O’Dell, RN