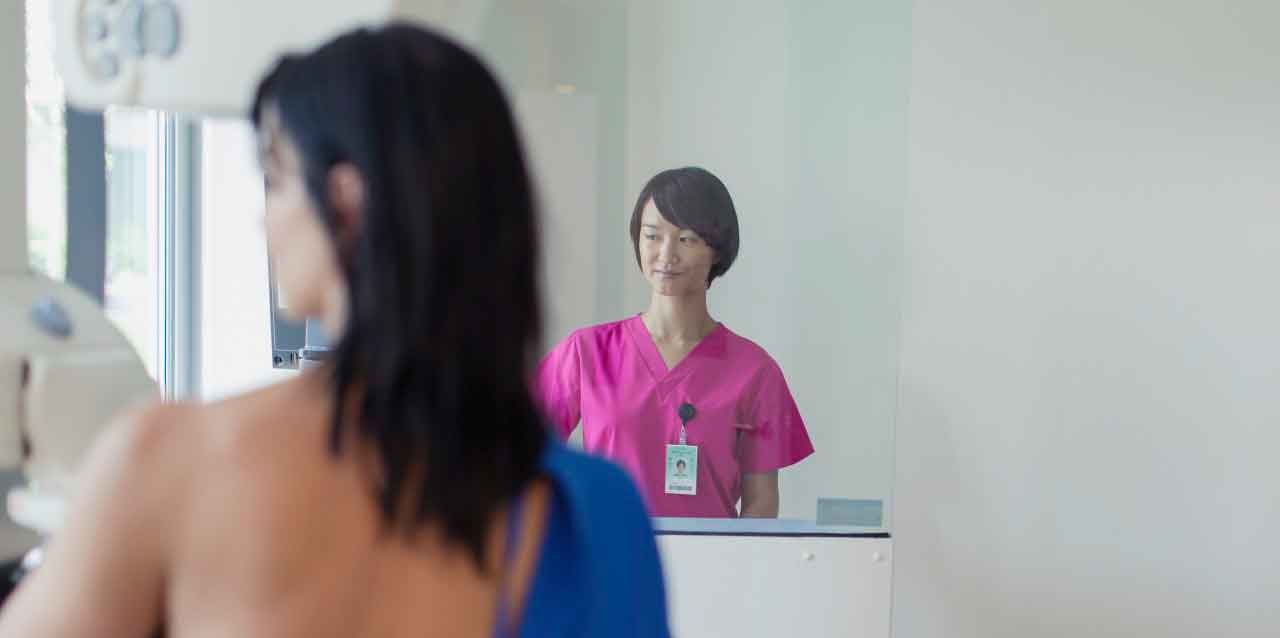

Anxiety Can Kill if You Avoid Breast Cancer Screenings

Fear of mammograms keeps some women from cancer checks.

Mammography, which uses low-dose x-rays to image breasts, can help find cancer at an early stage before women experience symptoms and when the disease is most treatable. However, mammograms aren’t perfect.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE: 8 Things Most People Might Not Know About Breast Cancer

A recent review of the subject, headed by Elizabeth Morris, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, noted mammograms can lead to over-diagnosing and over-treating breast cancers that would never be life-threatening. Mammograms can sometimes miss breast malignancies, too. But, far more often, the tests identify something as suspicious that turns out not to be cancer at all — and these false-positive experiences can cause enormous anxiety in some women.

In fact, being told a mammogram revealed something that requires more testing and possibly a biopsy for cancer can be so traumatizing, even when the final results show no cancer, some women decide to forego future mammograms. And that could be a potentially deadly mistake.

About 12 percent of women in the U.S. will develop invasive breast cancer during their lifetime — and around 40,450 will die from the disease in 2016, according to the American Cancer Society (ACS).The National Cancer Institute (NCI) points out that studies show screening with mammography can help reduce the number of these breast cancer deaths — especially among women ages 40 to 74.

(See the NCI website for additional information on mammograms. To find out how often you should have mammograms, the ACS recommends talking to your doctor about your risk of breast cancer and the best screening plan for you.)

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE: Older Women Need Fewer Mammograms

A study by researchers from the University of Colorado and New York University found a way to reduce anxiety about mammograms so women will hopefully keep having regular mammograms, even if they’ve had false-positive readings.

“Our intention was to teach women what to expect from having a mammogram done and what to expect if you are called back for further testing,” said University of Colorado Cancer Center radiologist Lara Hardesty, MD. “This happens to 10 percent of women, and we wanted them to know that a positive screening mammogram doesn’t mean you definitely have cancer. “

Hardesty, Jiyon Lee, MD, assistant professor in the New York University School of Medicine Department of Radiology, and colleagues tested their idea by developing a series of lectures to explain the logistics and outcomes of mammography. The lunchtime talks were presented to diverse business, religious, and community groups in the New York City area.

Before the presentation, the women in attendance filled out questionnaires about why they felt anxious about breast cancer screenings. Over half noted they worried about the results of mammograms, and 22 percent were concerned the procedure would be painful. Other concerns included worrying about the wait to find out about the test results.

But after the hour-long informational talk by radiologist Lee, a follow-up questionnaire revealed anxiety about mammograms had been reduced significantly. Almost all the attendees correctly answered questions showing they understood the benefits of mammography and the difference between needing additional testing and a cancer diagnosis.

Hardesty believes it’s crucial to screen aggressively for breast cancer in hopes of catching the disease at an early, treatable stage. “I personally have found breast cancers on the screening mammograms of many women from ages 40 to 45, whose cancers tend to be of a type that grow rapidly and act aggressively,” she said. “In cases where mammography discovers a cancer that is unlikely to be harmful, patients and doctors can still decide not to treat. In either case, it’s good to know.”

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE: The Frustrating Problem of Heart Disease in Women

Updated:

March 30, 2020

Reviewed By:

Christopher Nystuen, MD, MBA