The Surprising Power of Your Gut

Research on the forefront of medicine may provide long-sought cures.

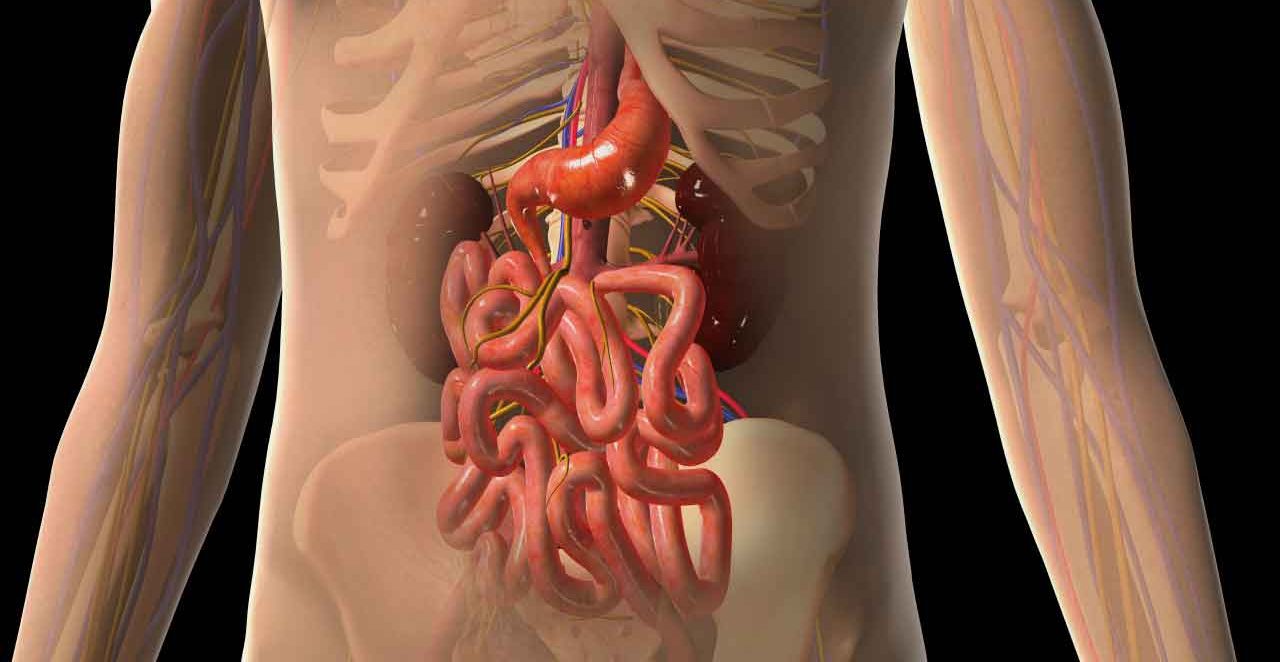

Scientists are exploring a new frontier: the human digestive system. It may sound startling, but this often-maligned aspect of human physiology may hold the key to some of medicine's most intractable problems. Some are calling it the most exciting area of medical research today.

The little-appreciated gut's 100 trillion microorganisms have long been understood to digest food and help protect our immune system. Yet science is finding the gut's bacteria, viruses, and other microorganisms — collectively called the microbiome — have surprising sway over the entire body. "The three pounds of microbes that you carry around with you may be more important for some health conditions than every single gene in your genome," Rob Knight, a professor at the University of California–San Diego and a leading gut researcher, said in a TED talk this year.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE: 12 Foods to Fight Constipation

In what researchers are calling the gut-brain-microbiome axis, the microbiome also helps produce dozens of neurotransmitters — the gut is the body's serotonin factory, for example, producing 95 percent of this essential mood-booster.

Scientists still aren't entirely sure how the bacteria and neurons in the digestive system affect the brain, and much of the work establishing the basis of these connections has been done in animals. But the results are so suggestive they've nearly single-handedly launched new fields of research, from microbial endocrinology to psychoneuroendocrinology.

What is clear is that the gut and the brain constantly communicate — and that communication is surprisingly two-directional.

Knight and others around the globe are just beginning to tease out the implications, but powerful research has already shown the brain-microbiome axis could be implicated in conditions like irritable bowel syndrome, obesity, and depression — perhaps even nervous system disorders such as multiple sclerosis and neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's.

To take one example, some antidepressant medications work by acting on serotonin. Yet it's long been noted that side effects of SSRIs include digestive problems such as constipation, diarrhea, and bloating. It could be that by altering the effects of serotonin in the body, these medications are also impacting the gut. Intriguingly, treating the gut directly might also lead to improvement in mood and well-being. Studies in mice show introducing beneficial bacteria to the digestive system in the form of probiotics reduces stress and improves depression-like symptoms. Small trials in humans are beginning to suggest the same.

Which is more accurate — do mood, diet, or other environmental factors change the bacteria in our gut, or do bacteria in the gut change our health? It may be that both affect one another, some researchers say. Either way, tinkering with the balance in the gut — via beneficial bacteria in the form of probiotics or microbial transplants — is looking like an increasingly plausible way to change behaviors long thought to be controlled by the brain.

In what may be one of the most surprising recent discoveries, researchers have shown bacterial transplants can change behavior. Working with two types of mice — one bred to be timid and another bred to be bold and gregarious — they found that when bacteria were transplanted from one type of mouse to the other, recipients took on the personality characteristics of the donor: assertive mice became more timid, and the timid mice began to more boldly explore their environment.

It's not just well-being over the lifespan that may be affected by the gut. Scientists postulate that a healthy microbiome is essential to normal brain development. Indeed, though the links are still fuzzy, studies suggest a possible connection between births by cesarean section and greater risk of subsequent development of obesity and autism. Birth through the vaginal canal, they say, provides contact with essential bacteria that help jumpstart the newborn microbiome — and, along with it, the immune system and the brain.

The links to autism are especially tantalizing. Researchers posit that diverse microorganisms in the gut may have helped the development of human societies by making it safe to gather in groups. However, mice raised in germ-free environments — that is, without gut bacteria — display brain and behavior abnormalities, including some autism-like characteristics: they don't interact with other mice and exhibit repetitive grooming behaviors. Treatment with a beneficial probiotic reduces such behaviors, and is more effective at doing so earlier in the life of the mouse. Researchers are exploring whether altered microbiota are a cause or an effect of autism.

Clinical trials are just beginning to test these hypotheses in humans. It's work at the very forefront of experimental medicine, and the results have been powerful. Yet they're also potentially dangerous. Consider the case of an increasingly common hospital-borne bacteria, C. difficile, which causes chronic, diarrhea. The condition can last for years, and doctors have found it particularly difficult to treat. In an oft-cited study, a fecal transplant from a healthy donor cured persistent C. difficile infections in 15 out of 16 people virtually immediately — after one infusion. Despite the ick factor, the procedure is believed to have a very high safety profile; reported side effects have been minimal, usually mild cramping for the first few hours.

Studies are ongoing — even exploding — in this area. The next decade may see significant advances. Yet researchers caution that much is still unknown. In the meantime, if you're interested in finding out what's in your gut, you can participate in the American Gut Project. For a $99 donation to science, the project anonymously sequences and analyzes your microbiome, comparing it to others in its growing database. Run by microbiome researchers at Rob Knight's lab, the project hopes to gather enough samples to draw rigorous conclusions about broad populations.

Updated:

March 25, 2020

Reviewed By:

Christopher Nystuen, MD, MBA