What Causes a Heart Attack?

The answer to what causes a heart attack may vary some, but always the flow of oxygen-rich blood didn't reach a section of the heart muscle. Here’s what you need to know.

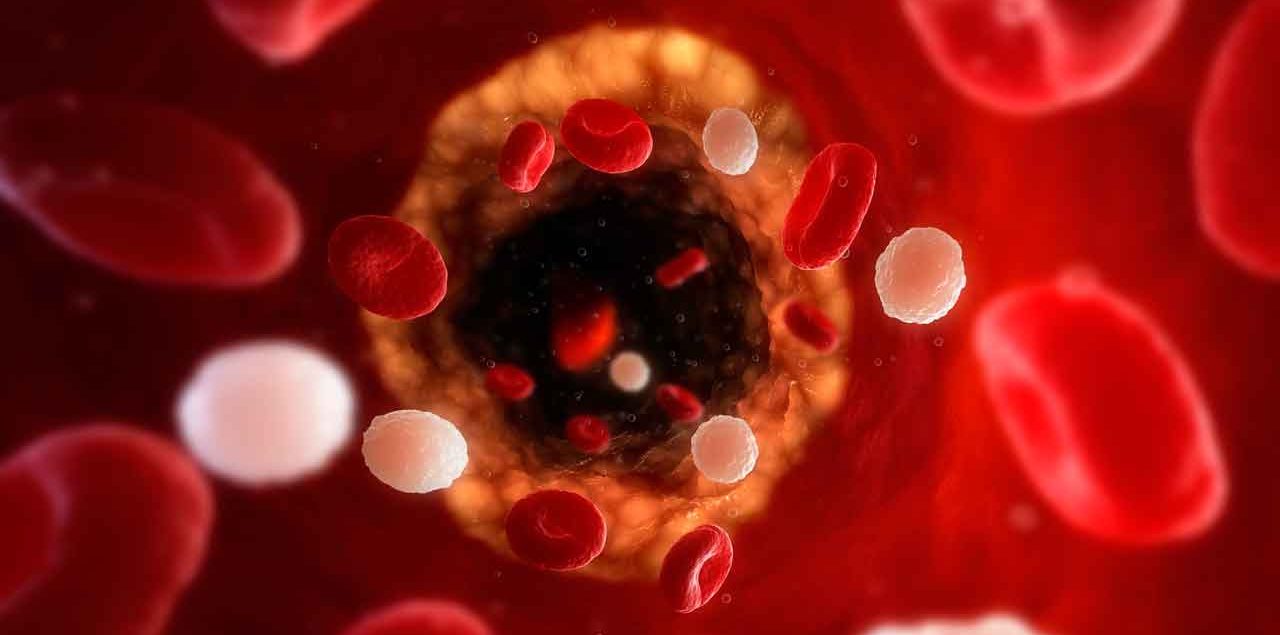

Most heart attacks are the result of atherosclerosis, a build-up of waxy plaque inside the arteries leading to the heart.

Atherosclerosis usually develops over many years, in response to many factors — smoking cigarettes, a fatty diet, obesity, lack of exercise, and diabetes increase your risk.

At some point, the plaque breaks open inside an artery. A blood clot forms on the surface of the plaque. If it gets big enough it can partly or complete block blood from flowing.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE: What Are the Signs of a Blood Clot?

The portion of heart muscle fed by that artery is starved for oxygen and nutrients, a state called ischemia. You’ve had a heart attack — technically called a myocardial infarction — when that part of your heart muscle is damaged or dies.

The overall name for this series of events is coronary heart disease (CHD).

If you are obese and have high blood pressure and high blood sugar you have what’s called metabolic syndrome, and you are twice as likely to develop heart disease.

Some factors contributing to heart attack are out of your control. You can’t help getting older. The risk of heart disease increases for men after age 45 and for women after age 55, or menopause. If your father or a brother was diagnosed with heart disease before age 55 — or a mother or a sister before age 65 — your chances are also higher. If you developed preeclampsia while pregnant, you are more likely to have heart problems later in life.

Sometimes we don’t know for sure what causes a heart attack. A heart artery can go into a severe spasm, tightening up enough to block blow flow. This can happen in both clear arteries and those blocked by plaque. Cocaine, cigarette smoking, emotional stress, and extreme cold are all possible triggers. In some uncommon cases, the wall of a heart artery tears.

Another unusual kind of heart attack, sometimes called “broken-heart syndrome,” is takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Japanese doctors gave it this name because the heart takes on the shape of a takotsubo pot used to trap an octopus. Lung problems or infections are the most common trigger. The next most likely is intense physical or emotional stress. But the trigger can be a mystery. You and your doctors may never know what causes a heart attack of this kind.

In a large multi-nation study of this kind of attack, the trigger wasn’t identified in more than 28 percent of patients. That study also found that 56 percent of takotsubo patients had a neurological or psychiatric disorder — compared to 26 percent of ordinary heart patients.

Many people think that every heart attack starts with a crushing pain in center or left side of their chest. Pain in that area is the most common symptom. But about a third of patients who have had heart attacks — often older women or people with diabetes — don’t have a chest pain. And your second heart attack may not come the same way as the first.

Women may think they have a flu — if they feel short of breath, get nauseated, and throw up or are unusually tired. You might feel a pain in the back, shoulders, or jaw.

“Silent heart attacks” are so mild you don’t realize you’ve had one until later. You might think you’ve had heartburn.

The heart is a tough organ. It will keep working despite injury in one section. However, a heart attack can cause cardiac arrest, when the heart isn’t beating properly. In one kind of cardiac arrest, the heart's lower chambers suddenly beat chaotically and don't pump blood. CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation) followed by a shock from a defibrillator can restore a normal heart rhythm within a few minutes and save the victim’s life. You can take classes in your community to learn how to perform CPR or operate a defibrillator.

Updated:

March 03, 2020

Reviewed By:

Christopher Nystuen, MD, MBA