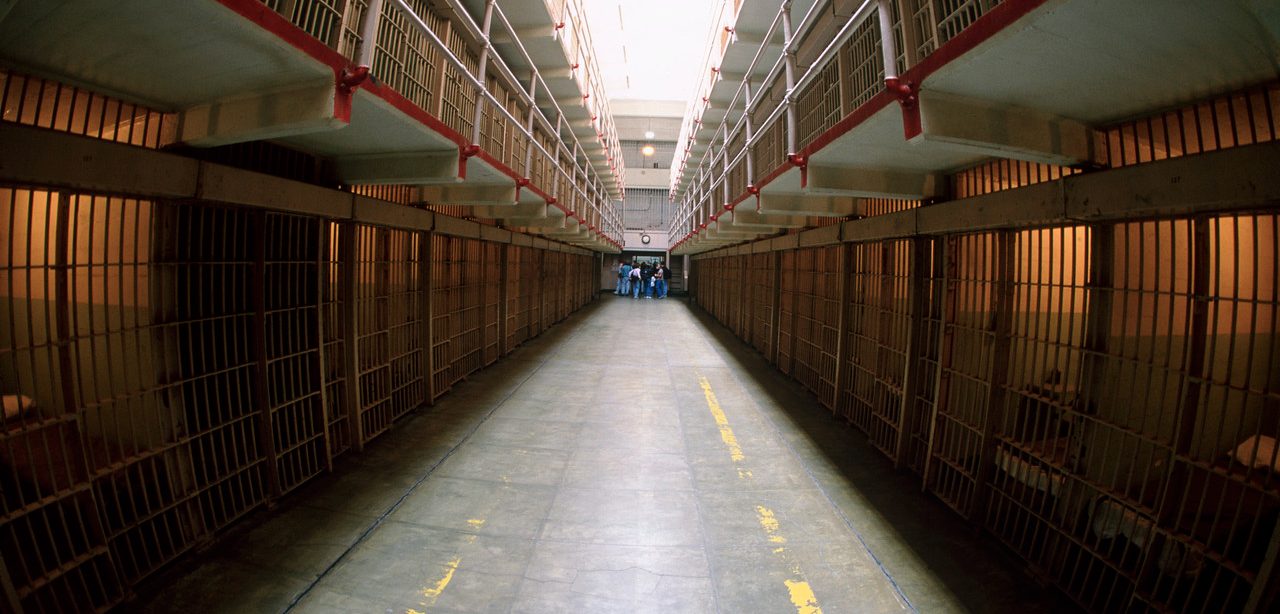

Jails Are America’s Largest Mental Healthcare Providers

More than half of those incarcerated nationwide may have mental health problems.

The severely mentally ill are now more likely to find themselves in jail — and inadequately treated there — than to receive care in the community.

"One can make an argument that psychiatric drugs are far overprescribed" for most people, says Jamie Mondics, communications director at the Treatment Advocacy Center. The nonprofit advocates for better laws and treatment for the severely mentally ill. But for people with severe mental illness, the opposite is true. Too often, Mondics says, they don’t get enough care or medication.

Those with severe mental illness — people with conditions resulting in psychosis, hallucinations, or delusions, such as schizoaffective disorder — often don’t recognize they are sick and are unable to pursue or maintain treatment unassisted. As a result, they are more vulnerable to harm and more likely to harm others.

Yet as funding for community mental health treatment has dropped in recent decades, the severely mentally ill are finding themselves with no place to go. States across the country have closed psychiatric centers in recent decades, dramatically reducing available care.

A 2012 report from the center counts just over 43,300 beds are now available nationwide for the severely mentally ill, down from a height of nearly 559,000 in 1955, when the deinstitutionalization movement for serious psychiatric care began. Meanwhile, just 35,000 people with severe mental illness are being treated in state hospitals — compared to a conservative estimate of 350,000 with mental illness now incarcerated nationwide, or about 20 percent of the nation's inmates. An earlier Department of Justice study found more than half of those incarcerated nationwide have mental health problems.

When trouble arises, those who are severely mentally ill, rather than being routed through the medical system, encounter law enforcement, and then are likely to end up in jail. “Of course, when somebody’s left untreated and deteriorating,” Mondics says, “they will act in a way that draws the attention of law enforcement.”

Law enforcement officers in most communities typically have few options. When leaving a person on the street will endanger themselves or others, they can only take a person to the emergency room or to jail. “Law enforcement is increasingly on the front lines of mental health. They receive numerous psychiatric calls every single day,” Mondics says. “And they’re not trained mental health professionals.”

In San Antonio, an innovative program is helping law enforcement address these problems while providing treatment. In a 40-hour training developed by Leon Evans, head of the city’s Center for Health Care Services, officers learn the symptoms of mental illness and skills for de-escalating encounters.

“Law enforcement officers are caught between a rock and a hard place,” Evans says. In his program, officers are taught “there’s something wrong with this person. They’re sick, and yeah, they’re screaming and they’re being threatening and stuff, but it’s not because they’re bad people. It’s because of their illness.”

The Treatment Advocacy Center argues that the severely mentally ill need treatment before they end up in jails, as well as adequate care while incarcerated. “But the ideal first step is to keep people with mental illness out of jail and prison in the first place,” Mondics says. “Jails are not meant to be psychiatric hospitals, so obviously the staff are not equipped to provide the treatment that people need, nor should they be. We should be putting people who need treatment in medical facilities, not jails.”

The severely mentally ill are far more likely to be the victims of crime than perpetrators of it, Mondics emphasizes. But untreated mental illness also plays a role in public violence. “When untreated, people with severe mental illness are likely to act on symptoms of their delusions, which is why some of these mass killings have taken place,” she notes. The Treatment Advocacy Center says about half of mass killings involve untreated mental illness.

In San Antonio, people with mental illness are evaluated at a city crisis intervention center and diverted to treatment. It’s a model being adopted elsewhere, one that saves $10 million a year while reducing jail populations. “Something’s wrong when the majority of people with severe mental illnesses are in jail and not in treatment,” Evans says. “It costs taxpayers a lot of money.”

“It’s better not to criminalize somebody in the first place,” he says. “We don’t put people with diabetes in jail, so we shouldn’t be putting people with mental illness in jail.”

Updated:

April 01, 2020

Reviewed By:

Janet O’Dell, RN