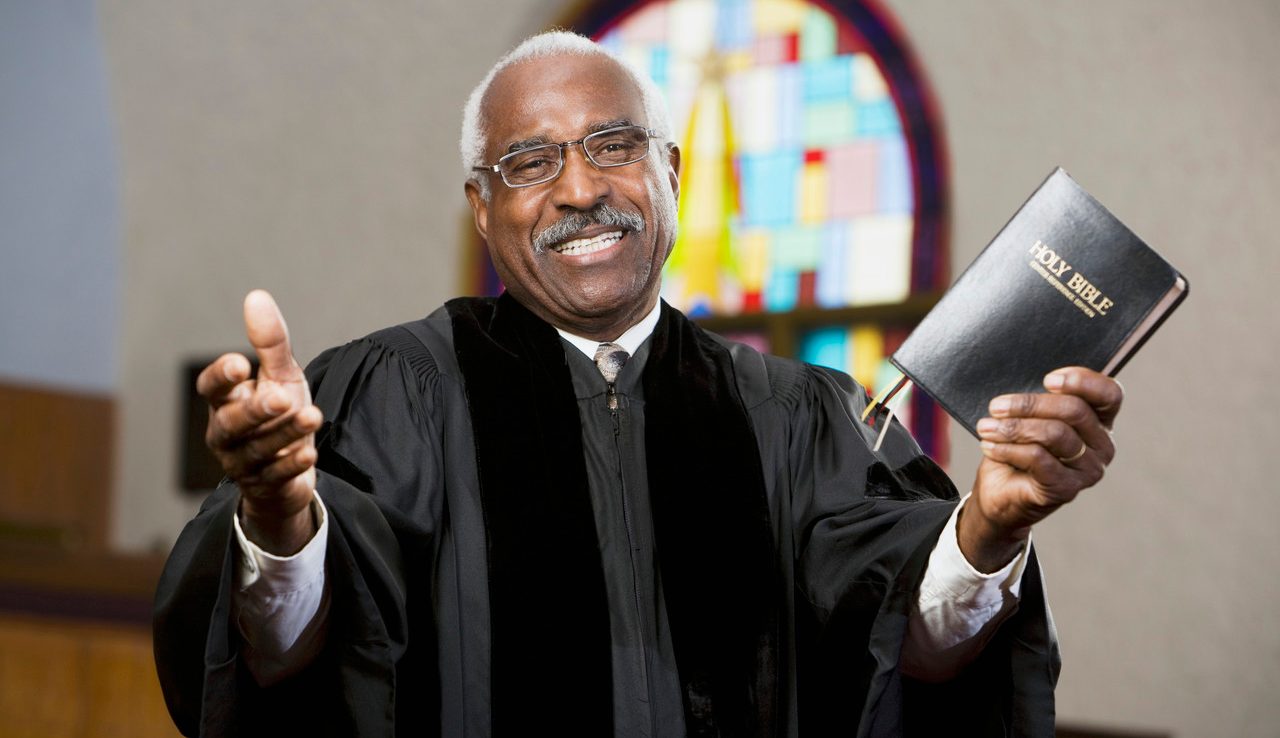

When Your Pastor Is Your Mental Health Counselor

A growing movement incorporates spiritual beliefs in mental healthcare.

Traditionally, those struggling with mental health or in trouble have often sought help at a church or place of worship. Many Americans still do.

In one national study, more people with a mental health issue had sought help from a clergy member (24 percent) than from a psychiatrist or general medical practitioner (both at 17 percent, respectively).

The divide between these two forms of care may be lessening as a result of efforts to coordinate care by both mental health professionals and religious leaders.

Spiritual leaders often refer those they counsel to mental health professionals, says Ryan Howes, PhD, a practicing psychologist and professor at the Fuller Graduate School of Psychology in California. “You ask any rabbi, they’ll probably have half a dozen names of therapists that they’ve referred to in the past, because they’re not necessarily trained in psychological issues and want to be able to help.”

And while the number of U.S. adults who do not identify with organized religion is growing, increasingly spiritual leaders may also refer to pastoral counselors. Six states now have specific licensing for pastoral mental healthcare. (Those states are Arkansas, Kentucky, Maine, New Hampshire, North Carolina, and Tennessee.)

The American Association of Pastoral Counselors (AAPC) is one group working to bridge the gap between religious counseling and mental healthcare. Founded to address mental healthcare in spiritual communities more than 50 years ago, the AAPC “wanted to consider a more holistic model that would take a person’s spiritual life seriously in the context of clinical practice,” says Douglas Ronsheim, the organization’s executive director.

AAPC members may be ordained clergy, Ronsheim says, but not all are. Members come from a variety of religious and spiritual backgrounds and are united by a shared interest in incorporating spirituality in clinical practice. All are licensed to provide mental health treatment in their state.

The AAPC is part of what Ronsheim says is a growing movement to integrate spiritual beliefs into mental health care. “Health-related sciences are becoming increasingly aware of the importance of spiritual life,” he says. “It’s not just pastoral counselors who are interested in the spiritual life of clients.”

In 2014, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) announced the Mental Health and Faith Community Partnership, a collaboration between the mental health and spiritual communities that provides education for clergy members. Ronsheim was part of the group’s steering committee. “The APA is increasingly interested in the spiritual variables of people’s lives and how that is an asset or a liability related to one’s mental health status. It’s not just siloed off. It’s increasingly seen as an important part of life and of people that needs to be engaged.”

While clergy take their counseling responsibilities seriously, they often don’t have training in dealing with serious mental health conditions or diagnosing when someone needs emergency care. The AAPC helps “faith communities — synagogues, mosques, temples, churches, and so forth — first, to be more aware of mental health issues and of substance use that are impacting congregants every day, and, secondly, how to better equip those faith communities to respond and support congregants,” Ronsheim says. “Historically, faith communities sometimes can be a big asset for people who are dealing with these issues, and unfortunately, other times they can be a detriment for people who are dealing with substance use and mental health issues.”

Many people find incorporating spiritual beliefs in mental healthcare helpful. Not only are many people more comfortable consulting spiritual leaders, but spiritual beliefs are often a source of purpose or calling in life. However, “there are other things in addition to religion that can help people have a greater sense of purposefulness,” Ronsheim notes. “So it’s really a complement.”

It’s also not essential that a pastoral counselor share a patient’s faith. What matters more, Ronsheim says, is that spiritual beliefs are acknowledged and incorporated into the therapeutic setting. Clients should “inform the therapist about their faith group and how that belief system is important to them,” he says. “We engage this like any other issue that’s presented in treatment.”

Pastoral counselors might help clients examine negative aspects of spiritual beliefs. “It’s not unusual for, let’s say, someone who was abused to also experience God as a punitive god,” Ronsheim says. “So one’s image of God and one’s image of self and one’s experience with important caretakers growing up all kind of flow together as to how one perceives oneself and how one perceives how others relate to them.”

To find a pastoral counselor, consult the AAPC’s directory of members, or inquire within your own spiritual community. Aetna Health and Value Options are two national insurers who work with AAPC members; local insurers may also have policies that incorporate pastoral counseling.

Unlike standard mental healthcare, pastoral counselors often have sliding scale fees intended to make care accessible to the widest range of people, Ronsheim says. “If someone needs services, it would be rare for someone to be turned away for inability to pay.”

Updated:

February 19, 2020

Reviewed By:

Janet O’Dell, RN