What the New Dietary Guidelines Mean for You

Shift to healthy eating patterns that replace bad fats and added sugar and salt with healthy fats and more fruits and vegetables.

As you try to digest the rather dense new dietary guidelines from the federal government, your primary takeaway should be making a lifetime commitment to healthy eating patterns.

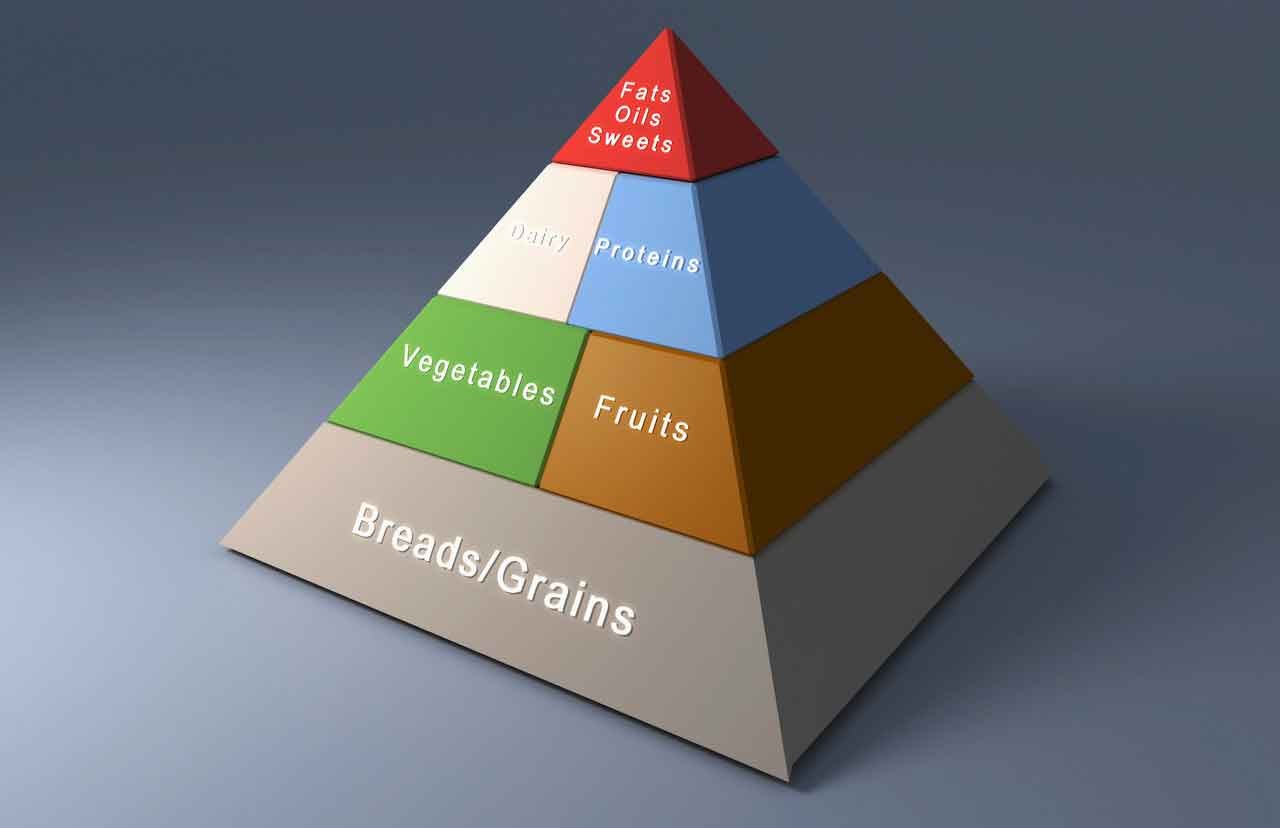

At a glance, the report recommends:

- Healthy eating is one of the most powerful tools you have to reduce your risk of disease, and most Americans can benefit from making small changes in their daily eating habits.

- You should eat more vegetables, fruits, whole grains, low-fat and fat-free diary, and lean meats and other proteins.

- Include more plant oils, such as canola, corn, olive, peanut, safflower, soybean, and sunflower. Also eat more nuts, seeds, and avocados.

- Limit saturated fats, trans fats, added sugars, and salt.

- Don’t forget to exercise.

- Everyone plays a role in healthy food choices, from the farmer to the grocer to restaurants to your table.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE: How to Cut Back on Sugar

First, the meat. In October, a report by the World Health Organization (WHO) put an exclamation point on the widespread clamor from health experts to cut way back on your processed and red meat consumption.

The WHO made processed meat a Group 1 carcinogen, meaning the cumulative research had concluded eating processed meats (like bacon) can cause colon cancer. Red meat was labeled Group 2A, the group saying that it is associated with colon cancer, but the relationship is less clear; the culprit may be the way people cook most meat instead of the meat itself.

Yet, the new dietary guidelines went relatively easy on meat. The report recommends eating a variety of protein sources, such as seafood, lean meats and poultry, eggs, legumes (beans and peas), soy products, and nuts and seeds. However, it also recommends you get less than 10 percent of your daily calories from foods containing high levels of saturated fats, such as meats not labeled as being lean. This instantly infuriated health advocates who wanted the WHO report and the cumulative evidence on processed and red meats taken into account.

"We are pretty disappointed the report doesn't recommend limiting red and processed meat because of the link to cancer," Katie McMahon of the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network told NBC News within hours of the guidelines’ release.

The guidelines do tippy toe up to the front line, but stop short by saying that “strong evidence from mostly prospective cohort studies but also randomized controlled trials has shown that eating patterns that include lower intake of meats as well as processed meats and processed poultry are associated with reduced risk of cardiovascular disease in adults."

Although the long-held recommendation to cut back on sodium (salt) remains a cornerstone of the dietary recommendations, it takes a back seat to sugar, whose consumption has concerned research far more in recent years, with studies linking high sugar consumption to increased risk of type 2 diabetes and heart disease, whether you’re overweight or not.

The guidelines say you should limit your daily sugar intake to no more than 10 percent of daily calories. That’s a major cut back when you consider that that average American reportedly consumes 22 teaspoons of sugar a day. That means you would have to cut your sugar intake by about half each day.

Still, the guidelines tell you to consume no more than 2,300 milligrams of sodium per day. The average daily sodium intake for Americans is 3,400 milligrams per day, according to the Food and Drug Administration, “an excessive amount that raises blood pressure and poses health risks.” Much of that creeps into your body from added salt in processed foods, such as frozen dinners, pizzas, and cured meats. Americans also tend to keep the salt-shaker on the dinner table during meal time.

Have a toast, or a roast, coffee lovers. The guidelines refer to the ubiquitous beverage for the first time. After years of good-for-you versus bad-for-you studies, the guidelines say that “moderate coffee consumption” (3 to 5 cups a day) can be part of a healthy diet because "strong and consistent evidence shows that consumption of coffee within the moderate range... is not associated with increased risk of major chronic diseases."

The guidelines advisory committee added that drinking coffee every day can reduce your risk of heart disease and type 2 diabetes, and may protect you from the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease.

Another aspect of the new guidelines that few seem to argue with includes the previous finding that there should be no limit on the intake of cholesterol from food. There was a previously recommended 300-milligram per day limit – the equivalent of about two eggs. However, “available evidence shows no appreciable relationship between consumption of dietary cholesterol and serum cholesterol. Cholesterol is not a nutrient of concern for overconsumption,” the guidelines say.

The guidelines say that three-fourths of Americans do not eat the daily recommended amount of vegetables and fruit, and that teenage boys and men get too much of their protein from meat, chicken, and eggs. To correct the problem, the guidelines say Americans should “reduce their overall intake of protein foods such as meat, poultry and eggs and add more vegetables to their diets.” Examples include dark green vegetables, such as kale, spinach, mustard greens, collard greens, and Swiss chard. Excellent red and orange vegetable options include squash, carrots, red peppers, tomatoes, and sweet potatoes.

If you want to boil it down to little bites from a big nutritional elephant, perhaps you should follow the now famous words of nutrition advocate and agribusiness critic Michael Pollan, author of “In Defense of Food: An Eater’s Manifesto.”

“Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.”

Or, “Don’t eat anything your great-grandmother wouldn’t recognize as food.”

Updated:

April 09, 2020

Reviewed By:

Christopher Nystuen, MD, MBA