The New Food Label

Processed foods may get a little less salty and sugary.

Do you check the nutrition labels on packaged foods?

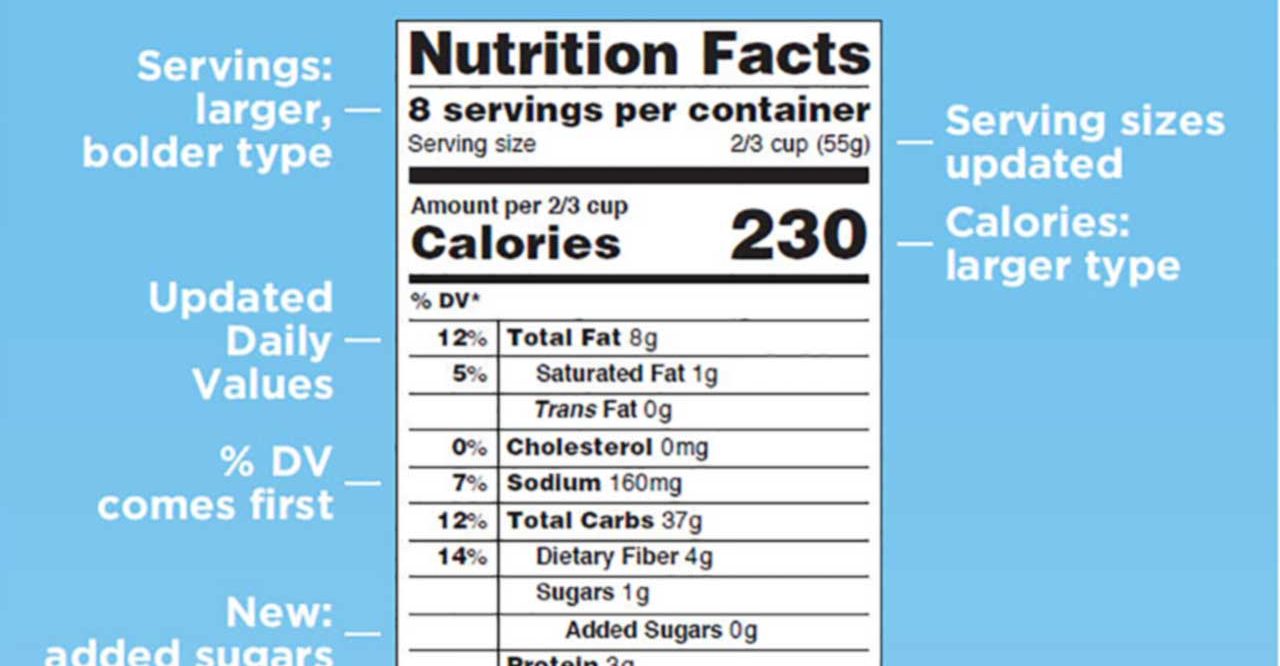

That little black-and-white box mandated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) will soon have a slightly new look.

Although it may not seem greatly changed, the new version comes to us after a multi-year debate, with input from the food industry, independent scientists, and consumers. The FDA’s main goal is to help Americans move towards eating fewer calories and less added sugar.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE: What the new Dietary Guidelines Mean for You

As Michelle Obama joked while announcing the changes, “Very soon you will no longer need a microscope, a calculator, or a degree in nutrition to figure out whether the food you’re buying is actually good for our kids.”

About half of Americans say they check the label frequently, and many more may now be curious to see how their favorite items stack up. We’ll see the revised label on most products by the end of July (some smaller companies have another year to adjust). Some 800,000 products currently carry a label, which was first launched 20 years ago. You also may find that familiar packaged foods taste a bit less salty and sugary, if their manufacturers alter them to avoid numbers on the label that could give consumers pause.

The most important label change: serving sizes are realistic. For years now, we saw information based on serving sizes much smaller than we usually ate — for most products — which made them seem healthier. Be careful not to eat or buy more, just because the serving size has increased.

Total calories, in an enlarged font, will now be impossible to miss.

We’ll see a new line — “added sugars” — to help us pick out foods that may not seem loaded with sugar at first glance. It also helps distinguish them from foods like fruit and milk that are sweet without an “added” boost. Sweeteners go by many names in the industrial food industry; now you don’t have to scan the ingredients for “maltose,” “dextrose,” “dehydrated cane juice,” “cane juice solids,” and other sugars.

The added sugar appears in grams. We’ll also see a percentage — how much that sugar would contribute to a recommended maximum daily intake. The maximum is set at 10 percent of a 2,000-calorie-a-day diet, which comes to 200 calories. So if the added sugar line reads 20 percent, the food contains 400 calories of added sugar.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE: How to Motivate Yourself to Keep Your Diet Resolutions

Who should eat 2,000 calories a day? A moderately active slender woman who doesn’t want to lose weight. But even an active 6-foot male who doesn’t need to lose weight shouldn’t eat more than 2,700 calories or so.

The added sugar information should be especially useful for parents, people who are prediabetic, sugar junkies, and bingers. Yes, you may already know you’re overdoing sugar, but the labels will quantify the damage even if you don’t get too detailed about the math. Will we be less likely to knowingly consumer 200 percent of our daily added sugar in one snack and go on to have dessert at dinner? That’s up to us.

We’ll also see per-serving and per-package breakouts on some items — a special message not to eat pints of ice cream or entire packages of cookies.

Packages that are between one and two serving sizes — for example, a 20-ounce bottle of soda — will now be labeled as one serving, so you can’t fool yourself that the bigger soda bottle isn’t really more sugar.

Foods may seem to contain less fiber and more salt — but only as a percentage of the recommended amounts, which have changed.

Information on vitamin A and C is no longer required, since deficiencies of these vitamins are less common.

If food scientists do their job well, we won’t mind that products have been reengineered to make them healthier. Kraft pulled off this trick — it removed artificial dyes in its macaroni and cheese three months before the company announced the change to consumers. No one noticed. Even better, we might come to appreciate healthier food.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE: Losing Weight Can Reverse Type 2 Diabetes

Updated:

April 09, 2020

Reviewed By:

Christopher Nystuen, MD, MBA